Thousands of miles north, Maine’s largest city faces a two-pronged crisis as a crush of illegal immigrants has overcrowded homeless shelters and created sprawling tent cities where crime and open drug use run rampant.

The city received more than 1,000 migrants between January and April, according to the city, many of which receive housing and public resources. There are currently around 225 tents making up Portland’s homeless encampments, and individuals inside the encampments, as well as an advocate for the homeless, told the DCNF that there aren’t enough resources to address both problems.

“The influx of asylum seekers has grown every year since Portland became a sanctuary city and currently the homeless shelter is full of asylum seekers,” Carol Waig, who runs nonprofit My Fathers Hands, which helps the homeless population in Portland, told the DCNF.

There were roughly 4,400 homeless individuals in the state of Maine as of January 2022, compared to roughly 2,000 in 2021, according to the Maine State Housing Authority, which says the sharp increase is “likely reflective of a surge in asylum seeking immigrants.”

The city recently created a new emergency shelter to free up 100 to 125 beds, according to its website. It also began busing migrants out of Portland in August, sending them from a temporary emergency shelter in a basketball arena to motels in other areas of the state, Lewiston and Freeport, according to the Associated Press.

“Our staff have been completely at capacity in terms of who they’re able to shelter and assist,” Jessica Grondin, city spokesperson, told the AP at the time.

“People from other countries come here, automatically get housing, get free care, free everything, it’s not right,” Bryce, who said he is homeless in Portland and that he came to the U.S. legally and went through a 10-year citizenship process, told the DCNF of the influx of migrants.

One large homeless encampment in Portland is filled with needles, naloxone used to reverse overdoses and needle disposal containers, the DCNF observed. Drug use is rampant among the camp, one of its residents, who went by Harold, told the DCNF.

“We’re human beings, we don’t want to be here, we really don’t want to be here, we don’t want to live outside, we don’t want to freeze the fuck out every night. Winter time on the Atlantic Ocean in Maine, do you think that’s comfortable when it’s below zero?” Harold said.

Some of Portland’s homeless have been offered shelter and haven’t taken the offers, Grondin told the DCNF.

“Through our [Encampment Crisis Response Team] process we have offered more than 150 shelter beds to people who are in encampments, but have not had overwhelming success in getting people into the shelter,” she said.

“We have expanded our outreach by using our own shelter staff and hiring outreach workers in order to get people into shelter as our focus is on getting people inside,” she continued. “It is our hope that our outreach efforts are successful so we can get people into shelter beds and other resources given that cold weather is now here.”

The migrant arrivals are also expected to continue given Democratic Maine Gov. Janet Mills’ August order to create an “Office of New Americans” and bring in 75,000 new workers by 2029.

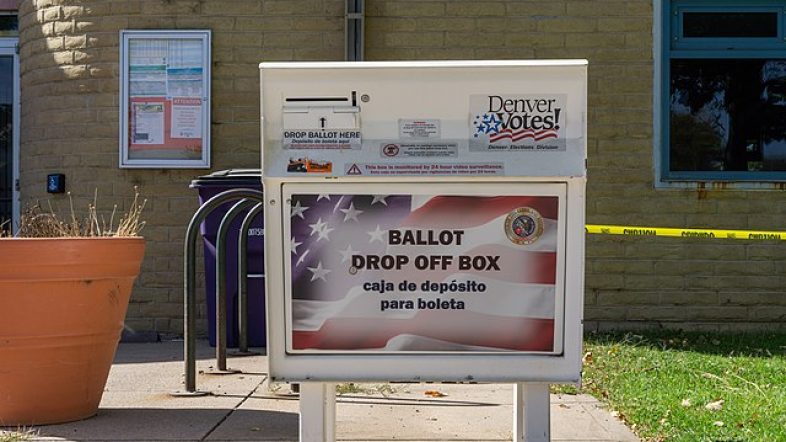

Syringe disposals sit in homeless encampment in Portland, ME. Jennie Taer//Daily Caller News Foundation

Jennie Taer//Daily Caller News Foundation

The city continues offering assistance to both migrants and the homeless, Grondin said in a statement to the DCNF. Both migrants and homeless qualify for the state’s General Assistance program that provides help paying for housing, fuel, utilities, medical care and burial costs.

City shelters housed an average of 1,200 individuals every night as of June, according to the city website. Some families are also being housed in a contracted hotel.

The city also opened a shelter, the Homeless Service Center (HSC), in March for 208 single individuals, in addition to the city’s family shelter, according to Grondin, who added that the city council in Portland recently “approved expanding capacity at the HSC by 50 beds.”

It is working to provide 120 beds at the HSC that the homeless in Portland’s encampments will have priority to take, Grondin said.

“Our goal is to connect those in encampments with those beds,” she said.

A spokesperson for Mills didn’t respond to the DCNF’s requests for comment.

Jennie Taer on December 2, 2023