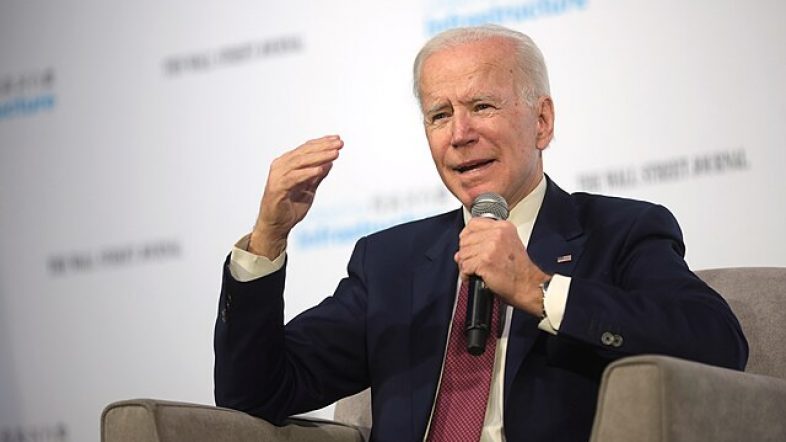

Available data and recent history contradict one of the key points of the Biden administration’s long-awaited study on liquefied natural gas (LNG) exports and Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm’s attempt to spin the study into something it is not.

The Department of Energy (DOE) released the study on Tuesday, nearly a year after the Biden administration froze approvals for LNG exports to non-free trade countries in January. The paper stops short of determining that more LNG export capacity is not in the public interest, but it suggests that significant growth in exports will drive up domestic natural gas prices despite all available evidence indicating that the exact opposite is true.

“The U.S. Department of Energy’s updated study finds that a wide range of domestic consumers of natural gas – from households to farmers to heavy industry – would face higher prices from increased exports,” Granholm said in a statement addressing her agency’s report. “The study put forward today finds that unfettered exports of LNG would increase wholesale domestic natural gas prices by over 30%. Unconstrained exports of LNG would increase costs for the average American household by well over $100 more per year by 2050.”

The study released this week is not the first DOE publication to suggest that growing LNG exports might bring about higher domestic prices: In 2012, the agency’s Energy Information Administration also projected a potential 54% increase in the wellhead price — the price of gas at the point of production — by 2018 in the event of a rapid introduction of new LNG export capacity. Between 2012 and today, a period in which American LNG exports accelerated massively, domestic natural gas prices fell as export volumes increased substantially, according to data analysis from the Chamber of Commerce.

The Shale revolution of the late 2000s and early 2010s prompted massive growth in the U.S. natural gas industry, but American LNG exports were essentially a non-factor prior to 2016, according to the Center for Strategic and International Studies. Today, the U.S. is the world’s leading LNG exporter and is on track to approximately double the LNG export capacity of Qatar — the world’s number two exporter — by 2028.

Granholm actually concedes that higher exports does not mean higher domestic prices in her assessment of the DOE LNG study, writing that “to date, U.S. consumers and businesses have benefited from relatively stable natural gas prices domestically as compared to those in other parts of the world who have faced far greater price volatility.” In effect, Granholm is stating that U.S. natural gas prices have remained “relatively stable” over the same period of time in which the American LNG industry blossomed into the global leader.

“There is zero evidence of any such correlation,” David Blackmon, a 40-year veteran of the oil and gas industry who now writes and consults on the energy sector, told the Daily Caller News Foundation regarding Granholm’s suggestion that more exports could lead to higher domestic prices. “It is abject nonsense.”

Moreover, Granholm also presided over a period of rising energy costs in the U.S., increases that energy market analysts like Travis Fisher, director of energy and environmental policy studies for the Cato Institute, attribute to the Biden administration’s $1 trillion-plus green energy and climate agenda.

S&P Global released its own study on the impacts of long-term U.S. LNG export growth on the same day that DOE put out its report. S&P’s analysis found that domestic natural gas prices have not increased despite massive export growth, and that the LNG industry has the potential to contribute $1.3 trillion to U.S. GDP by 2040, in addition to generating enormous tax revenues for the public coffers.

Nevertheless, Granholm contended in her assessment that her agency’s most recent “publication reinforces that a business-as-usual approach is neither sustainable nor advisable.”

With respect to sustainability, U.S. LNG — which is cleaner than gas from Russia, Qatar and most other places — is thought by analysts to have enormous potential to displace dirtier fuels like coal in other countries, thereby decreasing emissions relative to “business-as-usual” and maintaining energy reliability given the intermittent nature of renewables.

As far as whether or not it is “advisable,” particularly for investors and developers, to expand LNG export capacity, Blackmon said it is not the government’s role to determine which private investments are “advisable” or not. Instead, it’s the private sector’s responsibility to determine which investments make sense and which do not, with those who correctly read the market reaping the benefits while those who make bad investment decisions absorb the consequences of those choices.

“Not only is this not Granholm’s job, the study findings in the report published Tuesday simply do not support any such conclusion,” Blackmon said.

The DOE did not respond immediately to a request for comment.

Featured Image Credit: The White House