Several U.S. government departments will shut down in less than one week unless Congress passes legislation to fund them.

Under the terms of a continuing resolution passed on Nov. 15, funding for the departments of Agriculture, Energy, Veterans Affairs, Transportation and Housing and Urban Development will expire on Jan. 19 at 11:59 p.m. ET, leading to them shutting down operations unless funded by Congress. Though House Speaker Mike Johnson and Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer announced an agreement on Sunday to fund the government for the remainder of Fiscal Year 2024, that deal has been widely criticized by conservative House Republicans who have threatened to remove him from office should it proceed, prompting uncertainty about which course the Congress will take.

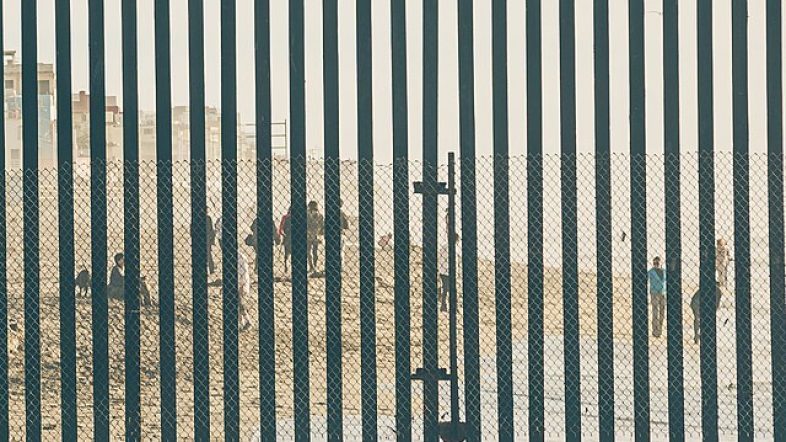

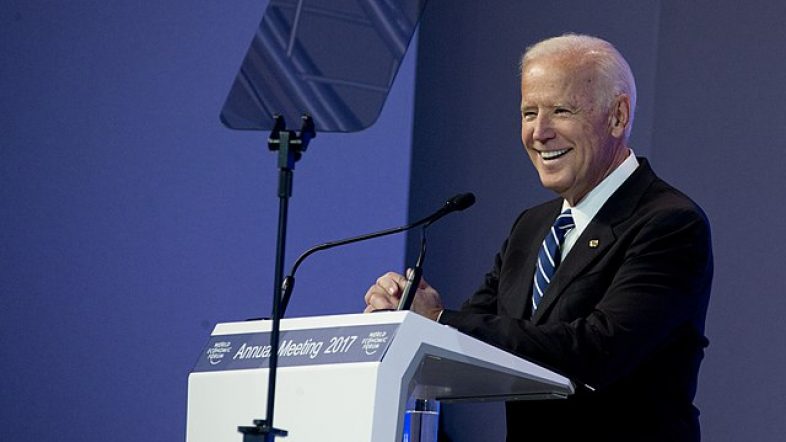

The deal between Johnson and Schumer calls for $1.59 trillion in spending until Sept. 30, at levels set out by the Fiscal Responsibility Act (FRA) of 2023, which codified a deal between President Joe Biden and then-Speaker Kevin McCarthy on the subject. Both deals have long been opposed by over 60 House Republicans, some of whom are now insisting on further cuts to spending and the inclusion of border security measures in the deal — failing which, they argue, the government should shut down — which have been vehemently opposed by Biden and Schumer.

To avoid such a shutdown, the House and Senate may enact a continuing resolution (CR) to authorize additional spending for a limited period while they resolve differences, which has been demanded by some senators. This course of action has already been undertaken twice — on Sept. 30 and Nov. 15 — and, if adopted, would break Johnson’s pledge to not consider any more CRs for the remainder of the fiscal year.

Many of the conservative Republicans who oppose the current spending deal have voted against the previous CRs, which maintain spending at levels established by the Democratic-led 117th Congress under the leadership of then-Speaker Nancy Pelosi. The Sept. 30 and Nov. 15 CRs received “nay” votes from 90 and 93 House Republicans, respectively, with some Republicans invoking the first such measure as a reason to remove McCarthy from office, which they accomplished with unanimous Democratic support on Oct. 3.

Were this third CR to extend beyond April 30, it would entail mandatory “sequestration” of funds under the terms of the FRA, whereby appropriated money is returned to the Treasury. Approximately 5% of non-defense discretionary spending would be sequestered, while defense spending would have a 1% cut.

Rather than a third temporary bill, Congress may pass a CR that covers the remainder of the fiscal year, which ends on Sept. 30, 2024. The idea has been endorsed by some fiscally conservative House Republicans such as Rep. Thomas Massie of Kentucky.

However, such a measure would also entail sequestration to the tune of 9% of non-defense discretionary spending, or $73 billion. These cuts, which would affect social spending programs, are unlikely to be accepted by House and Senate Democrats.

Defense programs under a full-year CR would not be sequestered, though the idea has been roundly criticized by Biden administration officials in the Department of Defense, who argue that keeping last year’s spending levels would harm national security. “A year-long CR would set us behind in meeting our pacing challenge highlighted in our National Defense Strategy—the People’s Republic of China,” wrote Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin in a letter to lawmakers on Dec. 12, 2023, adding that “[o]ur ability to execute our strategy is contingent upon our ability to innovate and modernize to meet this challenge, which cannot happen under a CR.”

Both the chair and ranking member of the Senate Appropriations Committee, Sens. Patty Murray of Washington and Susan Collins of Maine, oppose a full-year CR, indicating that a House-backed measure is unlikely to proceed in the Democratic-led Senate.

If Congress does not consider a CR of any length, it will have to either pass an omnibus spending package or, as intended by House Republicans, four separate appropriations bills. Past omnibus bills have been vehemently opposed by nearly all members of the House Republican Conference, who have long believed they preclude accountability about government spending due to their sheer length, which often runs into several thousands of pages.

Passing all four appropriations bills, by contrast, is likely impossible on the House’s current schedule. Congress is scheduled to reconvene on Tuesday, Jan. 16, after Monday’s federal holiday for Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Day, which will mean that both Houses have four days to pass all bills and present them to Biden for his signature.

“There’s nothing procedurally preventing the [Congress] from adopting all 12 bills. But given the disagreements…it would require a shocking turn of events to pull it off,” said Dr. Joshua Huder, a senior fellow of the Government Affairs Institute at Georgetown University, to the Daily Caller News Foundation.

The House has currently passed two of the required appropriations bills, while the Senate has passed three, with only one — the Military Construction, Veterans Affairs, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 2023 — being passed by both, though each house has passed a different version of the bill that will likely require a conference process to negotiate a compromise version.

“There just is not the time to do the work that’s necessary to get the bills done,” said Mark Harkins, another senior fellow of the Government Affairs Institute, to the DCNF ahead of Congress’ reconvening for the new year on Jan. 8 and 9. “This process is going to take weeks, not days…and they don’t have weeks when they come back, they have days.”

Arjun Singh on January 13, 2024