The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) recently issued yet another report on the rapidly deteriorating state of the federal government’s finances.

As Douglas Holtz-Eakin, a former CBO director, commented upon the report’s release: “The federal budget journey has arrived in Bleak with the fiscal course set for Hopeless. There needs to be a reset of the budgetary GPS, and fast.”

The speed and extent of the deterioration are exceptional — exceptionally bad, that is.

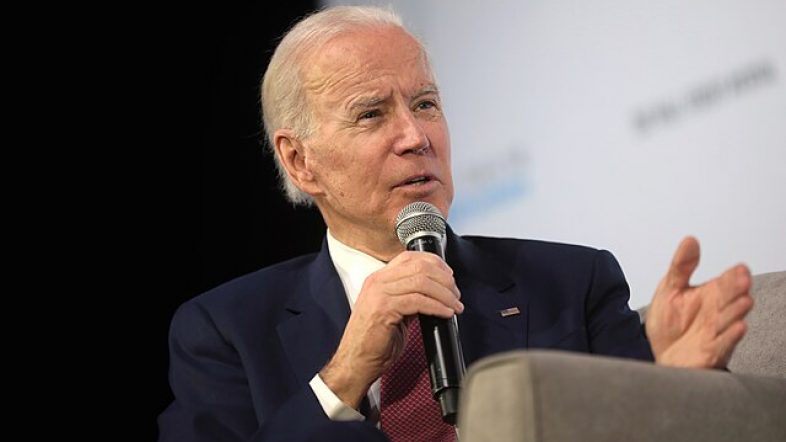

When President Joe Biden took office in 2021, CBO estimated the federal government would spend $5.258 trillion this year, resulting in a budget deficit of $905 billion. As of last week, reflecting the totality of Biden’s economic policies, CBO now estimates the federal government will spend $6.8 trillion this year (up 29% from the 2021 estimate) and run a deficit of $1.9 trillion (more than double the earlier estimate).

Words alone cannot convey the extent to which federal finances have deteriorated in recent decades, especially in recent years.

From fiscal years 1974 to 2008, publicly-held federal debt ranged from less than a quarter to just under half of gross domestic product (GDP). Policy analysts projected a large and sustained increase in the debt relative to GDP, but lawmakers were comforted by the knowledge that the day of reckoning would not occur for years.

Then came the Great Recession. It brutalized the U.S. economy, and years of debt were compressed into mere months. This raised the publicly-held federal debt to a level not seen since the late 1940s.

Publicly-held federal debt nearly doubled to 70% of GDP in fiscal year 2012 from 39.2% in 2008. The ensuing years featured a slow but steady increase in the federal debt as a share of GDP, reaching 79 percent of GDP just prior to the pandemic.

One saving grace of the Great Recession was that the run-up in the publicly-held federal debt occurred just as interest rates collapsed. This allowed the federal government to finance its debt at little cost.

Then came the pandemic and a federal spending frenzy that further ballooned the federal debt. Interest rates collapsed yet again, allowing the federal government to continue to borrow at rock-bottom rates.

But with the arrival of the inflationary Biden years, federal interest costs soared along with interest rates. This year alone, federal spending on net interest will total $892 billion — 36% more than last year and 153% more than fiscal 2021.

Unfortunately, the fiscal outlook dramatically worsens in the years ahead.

CBO estimates net interest outlays will jump another 14 percent next year and grow at an average annual rate of 6 percent per year for the next nine years. Given that nominal GDP is likely to grow more slowly, interest costs will increase steadily as a share of GDP.

Within 10 years, CBO anticipates annual net interest costs will exceed $1.7 trillion annually. The difference between what the federal government will pay in interest this year and what it will pay a decade from now is greater than Poland’s total annual economic output.

Factor in the projected increase in federal outlays for health care and other mandatory spending programs, and the federal budget increasingly spirals out of control. Rising deficits grow the debt, and the growth in the debt aggravates the deficit, further increasing interest costs. It is a vicious, debilitating cycle.

According to Phill Swagel, CBO’s current director, “It’s a slow spiral, but it’s still a spiral — of rising debt and rising payments on the debt.”

To avoid fiscal disaster, policymakers must act to stabilize the federal debt-to-GDP ratio through a combination of spending restraint and policies to accelerate long-term economic growth.

Most of the spending restraint must necessarily come from mandatory spending, as discretionary outlays are poised — and probably unrealistically so — to fall sharply as a share of GDP in the years ahead.

Spending restraint combined with faster economic growth will lead to a needed reduction in the deficit, producing additional savings in the form of reduced interest payments. This will further shrink the deficit. A virtuous cycle!

In Ernest Hemingway’s classic, “The Sun Also Rises,” Mike Campbell, a Scottish war veteran, is utterly penniless. Asked how he went bankrupt, Mike replies, “Two ways. Gradually and then suddenly.”

The federal government is the 21st century’s Mike Campbell. And, sadly, the country is experiencing, in real time, the transition from gradual bankruptcy to sudden bankruptcy. God help us.